While I have always viewed myself as a musical storyteller, I am not the first in my family to craft stories. My grandfather, Alan Cook, is an author and poet, shifting to writing full time with the publication of his first novel, “Thirteen Diamonds”, in 2000 a mere 8 months after I was born. Every birthday, anniversary, or major milestone is marked not just by a traditional gift, but also the accompanying poem to provide commentary and levity about the events leading up to the occasion. He even wrote a series of adventure novels starring me and my older brother Matthew, two of which (“Dancing with Bulls” and “Pictureland”) were later officially published. He is also the family lyricist for the song-alongs at the large Cook Family Thanksgiving gatherings in North Carolina, penning alternate lyrics to a variety of tunes (though some of his rewritings had to be sung by my professional opera singer brother due to their difficulty).

When I moved to Los Angeles in 2019, I was now much closer to him and my grandmother, his wife Bonny Cook, as instead of a 4-5 hour flight I now was just the length of the 110 away from them. It was during this time that my grandpa released Death at Monksrest in 2022, a murder mystery novel where amateur investigators Liz and Charlie travel to the Monksrest estate, so named as it is the legendary resting ground of four monks who were slain by their monastic brother in a fit of rage after a heated argument, after reading a poem titled “The Legend of Monksrest” about the incident. Almost immediately, multiple members of my family approached me about potentially writing music following the poem’s story, which I agreed to do. However, this request suffered from poor timing. My first attempts to write the piece were all miserable failures as I wanted to do the story justice, yet couldn’t figure out what I wanted it to look like. I tried a variety of different ideas and ensembles (including one attempt where I accidentally recreated the Olympic March), yet nothing would ever stick. And so, I put it off. I spent the next year completing my undergrad, constantly putting Monksrest to the side in order to focus on music that I had clear direction and vision for and after graduating, I entered a state of compositional semi-hibernation writing very little of anything, let alone the white whale Monksrest had quickly become. I had entered a mental cycle of knowing that I had to complete Monksrest, yet every time I would give it another go I quickly abandoned it again, all the while trying to answer the questions of various family members wanting updates about the piece. The breakthrough came in November 2024 when I revisited an old marimba ostinato I wrote for a film scoring class my sophomore year. When I wrote the marimba pattern I knew that I was going to revisit it somewhere down the line and now, with the 3 year anniversary of the original request rapidly approaching, I decided now was the time to finally lay the piece to rest. Almost immediately I could tell that this attempt was different as the music quickly fell into place and I was able to finally present something that was worthy of the expectations that I had thrust upon the work.The original version of this piece was around 7 minutes and I used it to help me get into CSUN to start my master’s. Almost immediately once I went back to school however, I grew dissatisfied with the version I had constructed. It was a decent bit of music, sure, but in the build to my first semester in Northridge I had rediscovered myself as a composer and, thus, the best thing I had written in more than 2 years was no longer good enough. I needed to reinvent The Legend of Monksrest in a way that befitted the composer I am now, and so when my composition instructor put out a request for early semester presentations, I volunteered and completely overhauled the piece in less than a week, almost doubling its length and deepening every aspect of the score. This is that version, the retelling of how an argument warped the mind of a pious monk, turning a peaceful pilgrimage into harrowing massacre.

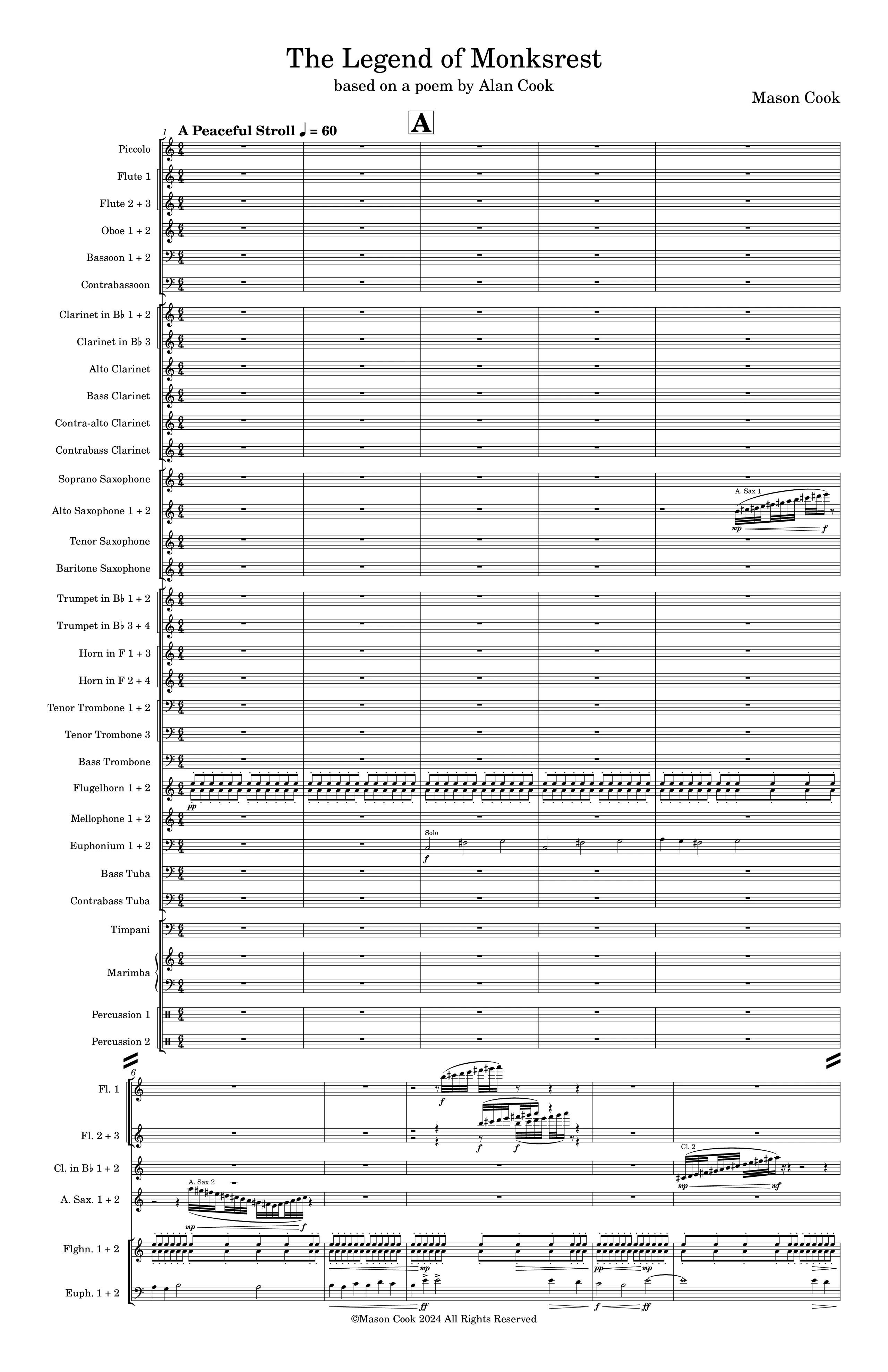

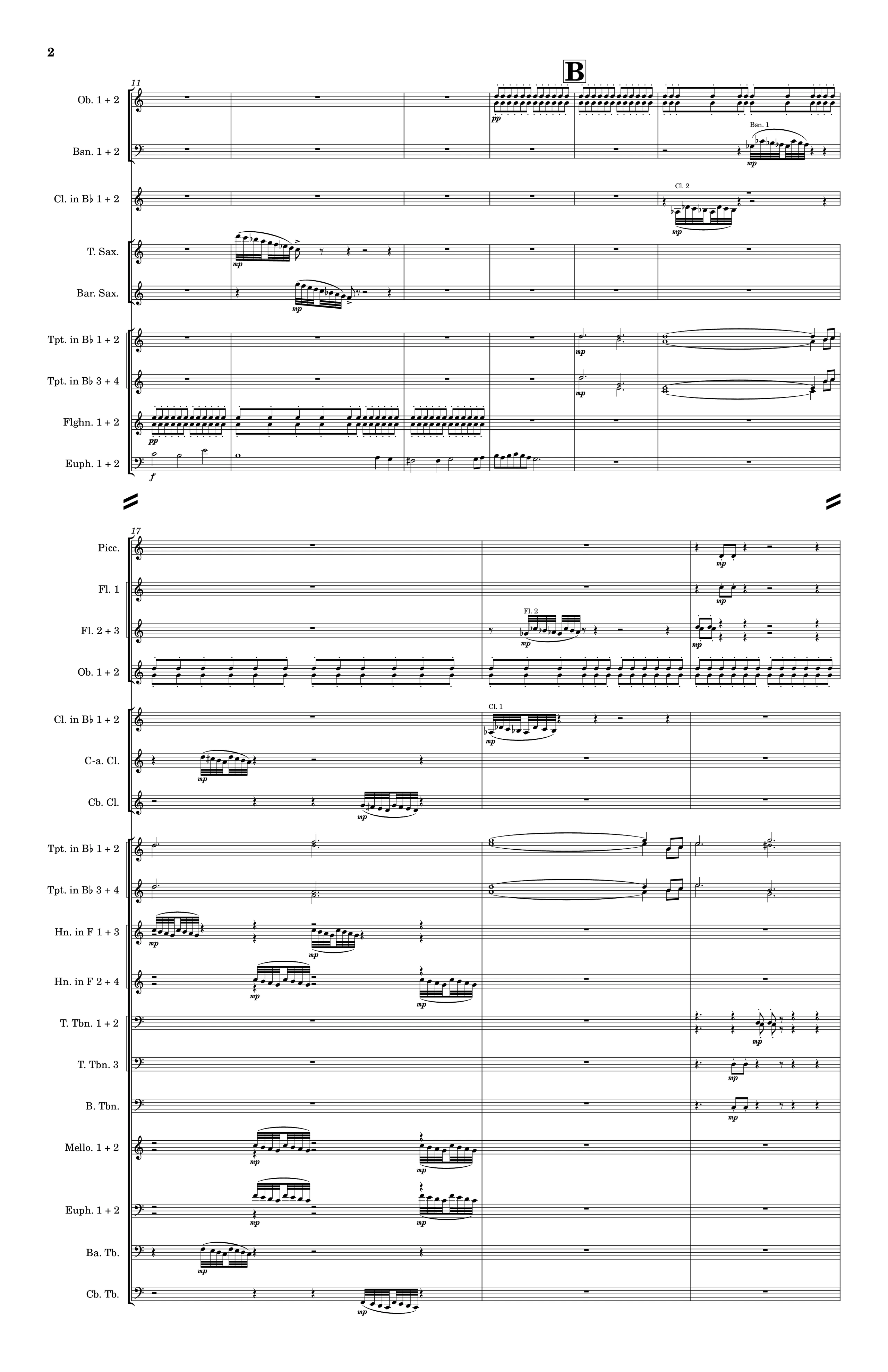

We start on a boring, uneventful walk through the English countryside, the slow, hypnotic eighth notes from the flugelhorns sounding under the euphonium solo before we are briefly introduced to the call to violence theme from the trumpets before we resume our walk, which quickly descends into a loud, chaotic argument. It is after this that we enter the mind of our eventual murderer, following his thoughts as they twist and turn trying to process the slights and disagreements he had with his four colleagues. We watch the conflict in his mind, the marimba mirroring the future killer’s sanity. First we see him work his way through his hurt and disdain, with the oboe solo planting the seed of self-rightuousness which eventually leads to the return of the call to violence, which the monk rejects. A further meditation occurs as the tenor and bari sax reflect on the nature of the disagreement and bring about a reassessment of how the monk views the conflict, leading to a reprocessing of his initial feelings, this time accepting the call to violence. We move to the deed itself, the knife being plunged into the defenseless pilgrims as the music gets faster and loses control, mirrored by the ascension of the piccolo to piccolo C, where we stay for an uncomfortably long time as the moment of realization hits our villain. Regretful, the music slows to a crawl as the killer attempts to give his victims a proper burial and curses the ground under which they are buried, ending on a quiet, mournful chord as we reflect on the crime. There is no atonement for the sins of the past, only remembrance.