0:00

0:00

0:00

Ensemble

1993

8 min.

More Details

- Program Notes

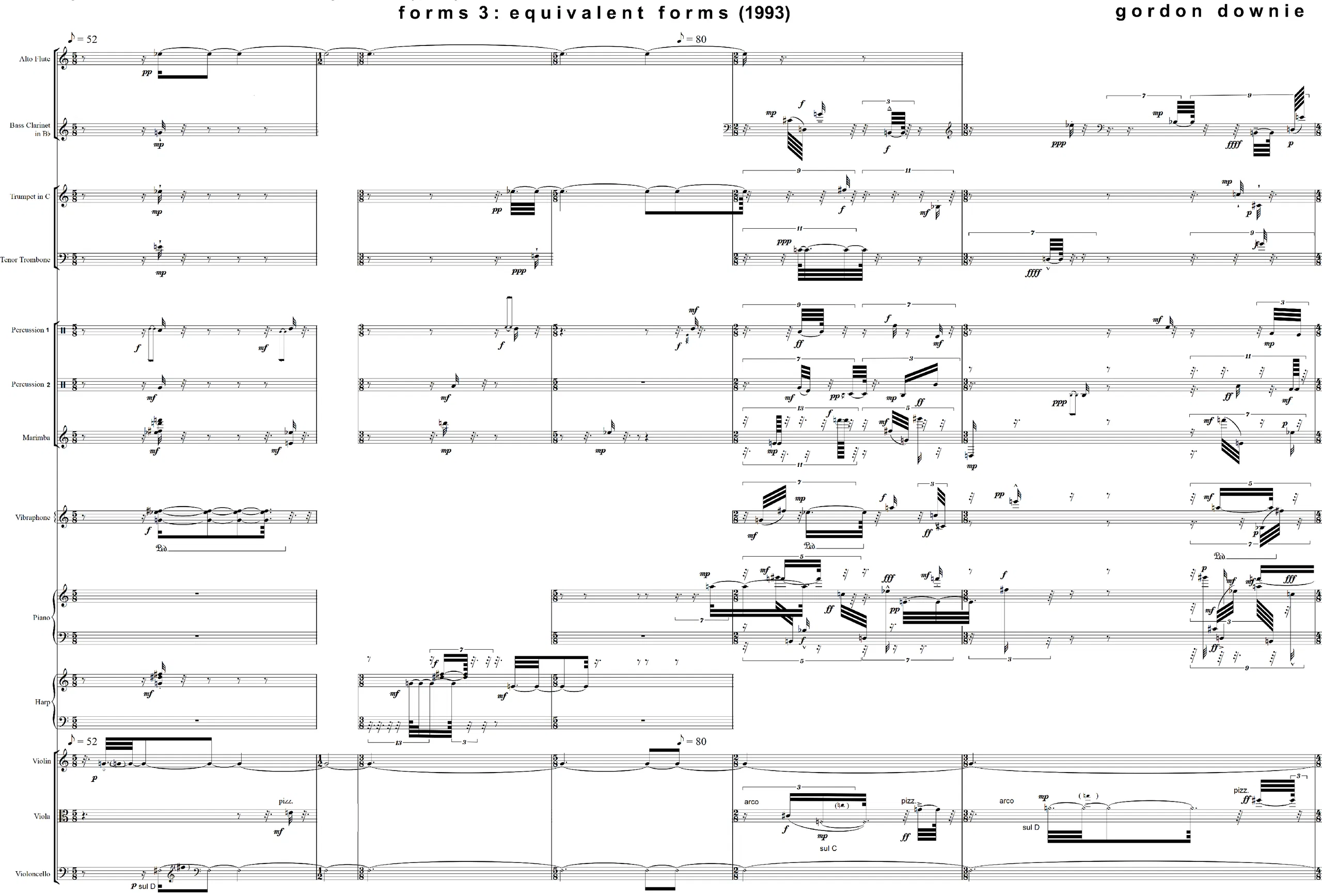

- Extract from Downie-Pace Interview, 2004. Ian Pace : What is the basis upon which you choose the particular configurations of instruments you employ? Gordon Downie : As I have already indicated, negation is one of the primary formal tools structuring my music. The choice of instruments is governed by this principle. Thus, the instrumental configurations that I use emphasise maximal timbral differentiation. This becomes more apparent in the larger works such as forms 5: event intersection and forms 6: event aggregates , where all instrumental families are represented. Within particular works, sub-ensembles also function as attributes or features of event types, which are also characterised by gestural profile, duration, tempo, and impulse-density, for example. Instrumental configuration is in this instance part of a wider organisational principle, functioning to control the progression of colour contrast and volume, and various levels of density and activity throughout the work. forms 3: equivalent forms , for example, is constructed from seven event-types and each is characterised by seven configurations of one, three, five, seven, nine, eleven, and thirteen instruments. Such organisational techniques are particularly effective projected within very large forces, as opportunities are created for superimposing such processes in very diverse and complex ways. forms 6: event aggregates begins this process which forms 7 will extend much further. IP : forms 3: equivalent forms for 13 players in particular seems to present a highly 'egalitarian' relationship between the different instrumentalists. Do you see any sort of innate hierarchies between instruments, and if so is this something you try to counteract? Would you consider writing a work for soloist and ensemble? GD : The suffix to forms 3: equivalent forms points to one of the main concerns of both this particular work and my practice in general. Though equivalence is a notion central to integral serialism, it is also a dominant conceptual tenet of many of the most significant movements in 20th century visual art and architecture, such as De Stijl; and Stockhausen's concept of mediation is essentially equivalence with another name, though more formally conceptualised. Equivalence posits the rejection of hierarchical structuring in favour of heterarchical structuring. In a heterarchical structure, all components are assigned equivalent status. This formal concern penetrates the organisation of forms 3: equivalent forms at every level, and accounts for the 'egalitarian' relationships that I attempt to establish in the distribution of the thirteen instruments. But this can only be achieved by demoting the primacy of pitch in order that percussion instruments such as temple blocks, wood blocks, and tom toms, can compete more equally with other members of the ensemble, in order to mediate between pitch and noise, or between the fully discrete and the continuous. This is achieved by employing pitch structures that exhibit a high level of invariance. There is little change or differentiation within this parameter throughout the work, which is formed almost exclusively from a single pitch class set, namely 3-3 using Forte's terminology. Through this form of cognitive saturation, listeners' attention is inevitably drawn to other parameters that are customarily subordinated or suppressed. This creates opportunities for instruments that are pitch-impoverished to contribute more equally to the musical argument. But other factors contribute to this process of pitch-demotion. The use of more or less densely articulated textures of sound, which are frequently opaque in quality, hinder the perception and definition of clearly delineated and precise pitch content. This is achieved by the use of either forward or backward temporal masking, whereby successive impulses mask or interfere with one another. This problematizes pitch definition. But with successful masking intervals being smaller than or equal to fifty milliseconds, we can only notate such effects indirectly and indeterminately, by superimposing different strata of mutually negating activity, the emergent complexity of which is a sum of that process of superimposition. This is how Stockhausen achieved some of the most effective, amorphous complexes in Gruppen , and it's a technique which contributes to the effectiveness of Gilbert Amy's use of two nearly identical ensembles in his Diaphonies : such effects are even more successful applied to identical timbre. In addition, forms 3: equivalent forms, tends toward using fewer long durations, a form of articulation not generally available to percussion instruments. As the discriminability of the frequency of pitches is reduced the shorter in duration they are, this feature contributes to the successful mediation of pitch and noise. Psycho-acoustics offers us a wealth of analytical and generative tools with which to explore these new sonic phenomena. But as I outlined earlier, processes of parametric foregrounding cannot occur in isolation: one must consider how changes in one parameter propagate and affect others, or consider that in affecting change in one, others may need similar levels of processing. Thus pitch-demotion is itself a multiparametric operation. If this is not taken into account, one will achieve the kind of nonsense that often passes for radical action: notating key-slaps or various forms of ad hoc distortion for woodwind and brass in the hope that pitch and noise can be successfully mediated (assuming the composer in question even realises this is what they are trying to do) only emphasises even more their oppositional characters. You are right to query whether my concern for structural equivalence could be consistent with the demands for hierarchy that inhere in soloistic or concerto forms. Clearly they would not, and it is for this reason that I have not so far explored this area. But I have often contemplated how it might be done, and several methods await further elaboration. These include the use of multiple soloists employing multiple timbres, or, perhaps more effectively, multiple soloists employing singular timbre, such as five harp soloists with ensemble. In a sense, one has to find a way to project a one-to-many form within a many-to-many conceptual framework. © Gordon Downie, 2004 Extract from Reflections, Critiques and Engagements: encounters with Gordon Downie and Zita Fabbri. Edizione Spaziale Critica Zita Fabbri: Can you elaborate upon the compositional techniques and structuring methods used in forms 3: equivalent forms? Gordon Downie: piano piece 1 and forms 3: equivalent forms employ similar methods. They were, of course, composed within a few years of each other. In considering their inter-connectivity, we need to consider what techniques were used to, as I stated earlier, maintain “high levels of similarity, invariance, or equivalence between structural and behavioural components, whilst simultaneously projecting them in ways that generate significant levels of differentiation and cognitive stimulation and sensation”. Within the context of pitch organisation, my interest was to construct a work using an interval organisation exhibiting a very high level of invariance and concomitant redundancy whilst extracting maximal differentiation within the imposed constraints using limited operations. Imposing high levels of invariance, or low levels of change and/or variability within one parameter, is one means by which higher levels of equivalence can be achieved between parameters. I outlined this approach in response to Ian Pace. In both works a single source trichord – (0, 1, 4) or 3-3 in Forte’s notation – and its’ transposed retrograde inversion is formed and combined to generate the source hexachord. The process of generating a retrograded and transposed form of this hexachord at interval class 6 furnishes the second hexachord to complete the aggregate. The operations of rotation, permutation, and hexachordal combinatoriality are then applied to the source series. Given the nature of this serial complex, there is already a high level of inbuilt internal similarity, correspondence, and equivalence between set components. The application of secondary operations such as rotation and permutation and methods of set intersection employing hexachordal combinatoriality, functions to maintain this high level of structural cohesion and identity with the underlying, original intervallic structure, whilst adding limited and controlled levels of differentiation. The rotation operator, for example, represents - after the standard operations of retrogradation and inversion - the most extensive transformation possible whilst maintaining the fundamental structural identity of the operand, here the series. This level of extreme cohesion is similarly applied to all other structural parameters, such as temporal and spatial assignments, impulse density, and so forth. I should stress that these concerns are represented in all my work from a variety of perspectives. Perhaps the focus here involves an attempt to retrain the user - the auditor - to respond to higher and finer levels of behavioural gradation. One might imagine that, if this process of retraining or reconditioning was successful, the levels of change and contrast customarily exhibited by music would be deemed incoherent and unintelligible, indeed intolerable. The structural constraints and organisation outlined here define sets of behaviours. Their reiteration creates predictive spaces that tightly control levels of cognitive stimulation, arousal, and expectation. Predictive spaces correspond to temporal windows within which events and behaviours occur, and define a duration, a time period within which certain behavioural constraints are operational. And such spaces are defined, in part, by those processes of desensitization that result from over-exposure and saturation to classes of stimuli. By closely determining the location and extent of behaviours that deviate from expectations generated by the predictive spaces, the precise temporal definition of such spaces can be complexly mediated. In consequence, cognitive stimulation is maintained, in part, by the extension and contraction of the time elapsing between the presentation of stimuli that do not conform to or frustrate expectations. The levels of difference exhibited by stimuli can be organised to operate within the subliminal to the supraliminal. Subliminal stimuli or processes are those to which the subject does not consciously attend, whilst supraliminal stimuli or processes are those about which the subject has more or less full awareness. Within each category are located objects, events, and processes. In this context, a subliminal stimulus is an object, event, or process that, whilst an essential element in the overall behavioural profile of the percept, is one that is subordinated or masked by, supraliminal stimuli the configuration of which require more immediate or urgent attention and/or processing. However, whilst subordinate, research indicates the extent to which such stimuli, nevertheless, make information processing demands, affecting processes of cognition and perception. This is a potentially powerful means by which to maintain stimulation, cognitive engagement, and arousal in contexts where the primary concern is extreme structural homogeneity and cohesion that strongly delimits the range of available and permitted behaviours and stimulants. Unlike the subliminal, whereby change is articulated at thresholds located below conscious perception, in the case of supraliminal stimuli, the levels of difference exhibited can be calibrated to mediate between stimuli exhibiting minimum differentiation, such as perceptual distinctions generated by a just noticeable difference metric, to maximum differentiation, however that might be defined. Subjected to permutation, such a range generates controlled levels of uncertainty, one of the primary mechanisms for generating forms of cognitive arousal and stimulation. Applied to a specific parameter, such as duration, subliminal stimuli are categorised here as sets of events or objects for which metrics are defined in milliseconds that, whilst resisting explicit differentiation, are nevertheless non-uniform. This can be applied to individual impulses or events. Applied to the former, duration classes define membership in terms of distance from a centroid calculated in milliseconds. In the following example illustrating a duration class comprising a collection of tuples, using 60 impulses per minute and the eighth note as the temporal reference, the centroid is defined as 70 msec and distance as any value ± 30 msec. This level of differentiation becomes more acutely effective operationally over the longer term in which the sample space is of a sufficient duration for these features to be established. © Gordon Downie, Zita Fabbri, 2024

- Recording Notes

- forms 3: equivalent forms for 13 instruments was premiered by the Contemporary Music Ensemble of Wales conducted by Gordon Downie at the Welsh College of Music and Drama, Cardiff in May 1993. Subsequently the work was featured in the Towards the Millennium series in April 1996 at the Concert Hall, Department of Music, University of Cardiff, in a live performance recorded by BBC Radio 3 and broadcast later that year. Instrumentation: Alto flute, Bass clarinet, Trumpet in C, Trombone, Harp, Piano, Marimba, Vibraphone, Violin, Viola, Cello Percussion 1: Guiro, claves, 5 temple-blocks (high to low), 2 bongos (high, low). Sticks: hard Percussion 2: chocolo, maraca, 5 cowbells (high to low), 3 woodblocks (high to low), 2 timbales (high, low), 3 tom-toms (high to low). Sticks: hard

- Ensemble Name

- Contemporary Music Ensemble of Wales